Post by Greg MacAyeal

Curator of the Music Library, Northwestern University

Member, MLA Legislation Committee

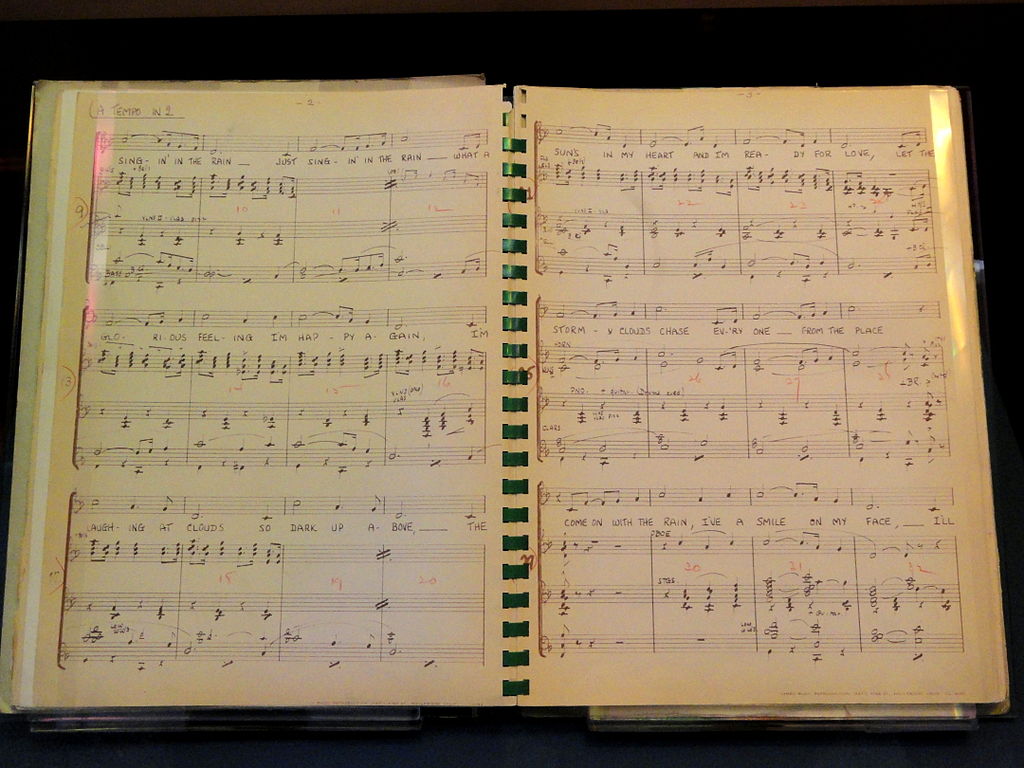

One of the clearer areas of copyright law is the definition of “original work of authorship” (US Copyright Law, section 102). Still, researchers and librarians may find themselves in muddy waters. While some works may be easy to define this way, like a book, a play, or a musical composition, some works require scrutiny on the concept of “work” itself. Such is the case with conductor’s annotations. Markings on a printed score give an indication of the conductor’s interpretation and may be useful for research. Some conductors are known for a particular orchestral sound, or for their specific interpretation of an individual composer. The annotations are manifestations of the conductor’s expression. But, are they “original works of authorship”?

Finding a definition is important for archives holding conductor’s scores, like the Leonard Bernstein Collection at Indiana University or the Annotated Mahler Scores of Maurice Abravanel at the University of Utah. A project at Northwestern University’s Music Library is on hold while the staff waits for university general counsel to offer a legal opinion. Northwestern’s Fritz Reiner Collection contains hundreds of the maestro’s annotated scores of composers like Beethoven, Mozart and Bartók. To this day, many feel the Riener recordings of Richard Strauss’s music (RCA and Columbia) are definitive. Northwestern would like to make the Reiner annotated scores available to the public, enabling an experience of Strauss and other composers that pairs the recording with the annotated score. To be clear, the printed score itself is an original work and its use fits neatly into the guidelines of copyright law. The annotations by themselves bring copyright ambiguity. Without being able to define annotations as original works of authorship, the library is unsure how to proceed. If they are not original works, they are not protected by copyright. The concept of “original work of authorship” does not apply. If they are original works, the library must develop the project within the boundaries established by copyright law. The project can move forward in either case, but the path taken will be different. The awaited legal opinion will tell the library which path, and without an opinion, the project is on hold.

Like many copyright concerns, finding a solution depends on the context of the material, use, and setting. Some libraries take a very limiting approach to copyright issues while others are quite permissive. Opinions can vary greatly, but simply getting attention from legal counsel can be difficult. The project at Northwestern has been waiting for a legal opinion for more than two years.

The New York Philharmonic Digital Archives offers an interesting and assertive path forward based on the principle of Fair Use (US Copyright law, section 107). Many of the scores themselves remain under copyright protection and include annotations. Under a “Rights, Permissions and Publishers” section of the site, NY Phil asserts the scores are made available for study and research only. All other uses may require permission and conveniently, contacts are provided for many publishers. The notice serves as an indemnification at the same time moving a fair use argument to the forefront. The archive is protected, the scores are available, and users are then responsible for any required rights analysis.

While it still may be important to consult legal counsel, there are many resources offering assistance as library staff navigate these complicated matters. The Legal Information Institute of Cornell University is an excellent source for copyright definitions.

Please see the MLA’s site for more resources:

https://copyright.wp.musiclibraryassoc.org/copyright-resources/